The Exhibit

“If you were to go to Europe, you would everywhere feel that you were in a strange land, but still many things would remind you of your own dear home in America. But if you were to go to Asia or Africa, the houses, the fields, the dress of the people, and all their manners and customs, would impress you with the idea that you were in a strange land, far, very far, from your native country.” — Samuel G. Goodrich. Peter Parley’s Universal History, on the Basis of Geography. Boston: American Stationers’ Company; John B. Russell, 1837. p. 1:183.

When and how and why did the United States globalize? We can start answering this question by looking at the remarkable publishing career and unremarkable diplomatic career of Samuel G. Goodrich, whose life spanned the telling era between the American Revolution and the American Civil War.

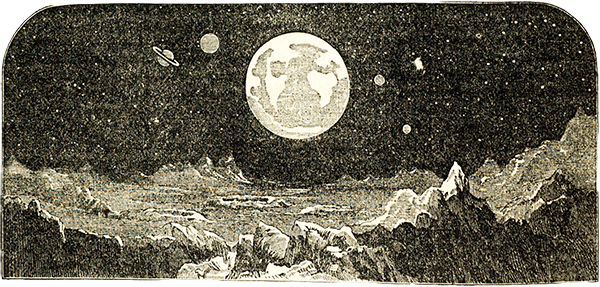

In 1851 Goodrich published another of his 170 books for the American youth market, this one a weighty two-volume set entitled A History of All Nations, from the Earliest Periods to the Present Time. An early page featured an engraving of “The Earth as Viewed from the Moon” which anticipated, by more than a century, the epochal color photograph taken of the Earth during the 1968 Apollo 8 mission’s orbit of the Moon — the famous photograph known since as “Earthrise.” The 1851 earthrise engraving, as imaginative as it was, would not be epochal in its moment of American history. It was routine then to blend astronomy, geology, and geography into a long view of history, and it was routine then to encompass the entire globe in American schoolbooks. Americans were imagined to be global already from their youthful studies.

Or so they should have been. A prolific author who boasted seven million books in sales, Goodrich did his mite to persuade Americans that it was worth their children knowing the wider world, to help the nation become ever more potent in that world. Goodrich was not alone in this quest to enlighten the public while enriching himself. From the aftermath of the American Revolution forward, the places and the peoples of the world would draw increasing public fascination and policy debate in more popular as well as more arcane books: travel narratives, political tracts, business manuals, missionary testimonials, navy chronicles, scientific reports, and more. Bookstores and libraries filled up with spectacles and dramas of the world, as did bookshelves in homes.

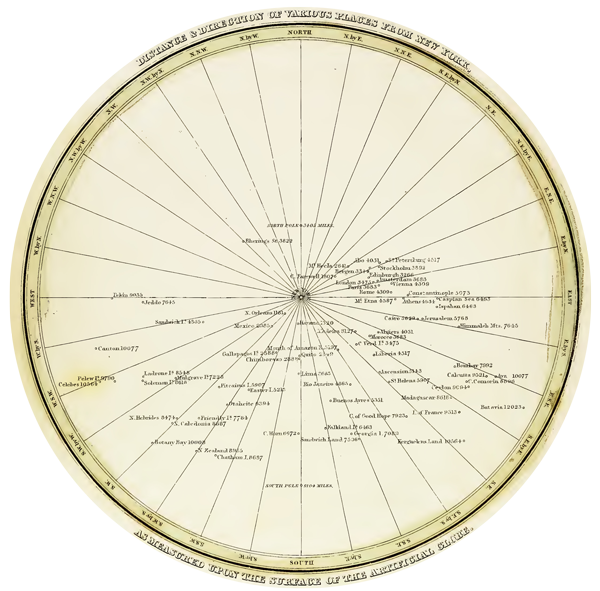

That “world” was initially, in the 1790s, all too nearby in the form of the British empire to the north, the Spanish empire to the south, and Native American nations to the west. Another portion of the “world” was long familiar in the form of western Europe across the Atlantic Ocean. Everywhere else on the globe seemed remote and exotic. Yet by the 1830s the “world” put into focus for American readers extended to greater and greater distances: to South America, to Africa, to the Pacific Ocean, to Asia. An 1835 American atlas located the place farthest in the world from New York City at 12,023 miles away, but the graphic’s implication was that every location on the globe was within view of the United States. American reach into the world had become truly “global” on multiple fronts — diplomatic, commercial, military, missionary, and scientific — so that the United States had been transformed from a decolonized backwater into a world power which thought of itself as second only to the British empire in global stature.

Alive from 1793 to 1860, Goodrich witnessed this global expansion of the United States, and he celebrated it in his many nationalistic schoolbooks. Yet he viewed “globalization” principally as an American as well as a British enterprise; the modern steamships traversing every ocean by the 1850s emanated mainly from these two countries. The United States may have been connecting itself to the wider world, but the world was not connecting itself to the United States. Who had attained the power to act at global distances to advance their interests? Who had attained the power to protect their sovereign homelands from outside interference? Out of all the nations in the world, really only Britain and the United States could do so, according to Goodrich. He told a story of imperial reach, not global interconnection.

And Goodrich told a story of cultural incommensurability between Americans and Europeans on the one side, and the rest of the world on the other. Only Europe was recognizable to America, as a place and as a people. Everywhere else in the world appeared demonstrably and enduringly alien — even if no longer as remote as it once was. Goodrich’s prejudice was reinforced by his own limited experience of the world. As a younger man he sojourned in Britain and toured Europe; as an older man he served as U.S. Consul in France. Even so, he blithely positioned his millions of young readers as armchair eyewitnesses to the globalization of the United States, who could master the world without ever having to venture out into it.

But Goodrich’s was only one American voice and enterprise among many. The key to American pursuit of empire and globalization in the first half of the nineteenth century was the sheer growing variety of the young nation’s activities in the world: diplomatic, economic, military, religious, scientific, and more. It was not Goodrich but his many readers, and many more Americans beyond his impressive readership, who transformed the United States from a fragile and marginal country into a “great power.”

It was the cumulative effect of those many Americans — the ones who ventured beyond the country’s borders and the ones who did not — which resulted in something we today might interpret as “globalization.” We cannot understand “globalization” if we do not study what arguments and activities managed to produce it, to advance it into the world. And we cannot understand American history between the Revolution and Civil War if we do not gauge nation against empire and against wider world.